Etchings

I am drawn to the etching process because I think it’s the ideal way to use an art form to recall and imprint lost memories. The etching processes I use creates and prints images that are intentionally ethereal to be in conversation with memory rather than a direct copy. When making these etchings I am trying to fill in the gaps and study the fragments of memory. I depend on techniques like this to remind me that though it is not possible to see exactly what my ancestors have seen, I can maybe catch a glimpse and experience life the way they might have.

The photo-secessionist movement of the early 20th century, where many photographers created images with a more ethereal, painterly quality, plus the heartbreaking fact that it’s impossible for me to see the same things my ancestors have seen, are the inspiration behind using this process. This form of mark making ensures that these recovered memories will not be lost again.

Copper Photogravures

Memory Index: Imagined Family Heirlooms

This series of copper photogravures explore the migration of the artist's ancestors through objects she imagines might have belonged to an ancestor or objects that existed in the space where they once lived. The artist’s original photographs are printed on the her handmade paper made from a combination of raw cotton from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina and palm fronds from Cameroon. The intentional soft focus of the images is meant to be in conversation with the fact that the artist is attempting to see what her ancestors might have seen, but knowing that’s impossible. The title of each piece is taken from an archival manuscript related to her ancestry.

Copper photogravures printed on handmade paper made by the artists using a raw cotton from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina and palm fronds from Cameroon

1880 United States Federal Census: French, Martha | Widow

2024

This piece imagines a moment following the extended family’s initial migration from Kentucky to Chicago in 1866 after the death of the artist’s great-great-great grandfather in 1873. I imagine his wife wore a mourning bonnet like this one. Now a free woman living in the North, she was able to always express herself in ways, even through fashion, that she was unable to do in the past. It is printed using bone black ink using an etching process on the artist's handmade paper to permanently mark the memory so this moment in time won’t be forgotten again.

Title: Nancy, a Girl, 1790

2024

The artist’s great-great-great-great grandmother Nancy grew up on the Kentucky frontier before moving to Montgomery County, Kentucky. The title of this piece is taken from the 1790 will of William Hoy, who was present at Fort Boonesborough with his family and those he enslaved, men, women and children who managed his household, in the years before Kentucky’s founding, along with Daniel Boone. The artist slightly altered the wills original text “Nancey, a Negro Girl” to do what she could to reclaim the narrative about her ancestor. She selected an antique frontier knife to represent Nancy in this series to show that life on the Kentucky frontier was fraught with danger on all fronts for a young enslaved girl during this time and that someone in her position should always be ready to protect herself.

“… beautiful ladies attired in the most magnificent costumes…. black lace, ostrich tips” The Appeal, January 20, 1889

2024

The African-American weekly newspaper covered a lavish party hosted by John B. French, the brother of the artist’s great-great grandfather David French, in Chicago in 1889 at their “new and elegant residence … [at] 1002 Walnut Street.” In attendance was former Louisiana Governor P.B.S. Pinchback who was the first African-American Governor in the United States. The article gives a rare look into a part of African-American society during this era that is not often shown or discussed en masse.

Title: Accepted for Enlistment at: San Francisco; Enlisted on: November 13, 1913

2024

A large pine cone collected from the forest floor in San Francisco’s Presidio, a former Army base where the artist’s ancestor, Lt. William J. French, was stationed and eventually buried in 1932. The pine cone came from a tree that existed when William lived at the Presidio.

The below copper photogravures were in the triennial Bay Area Now 9 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, CA

.

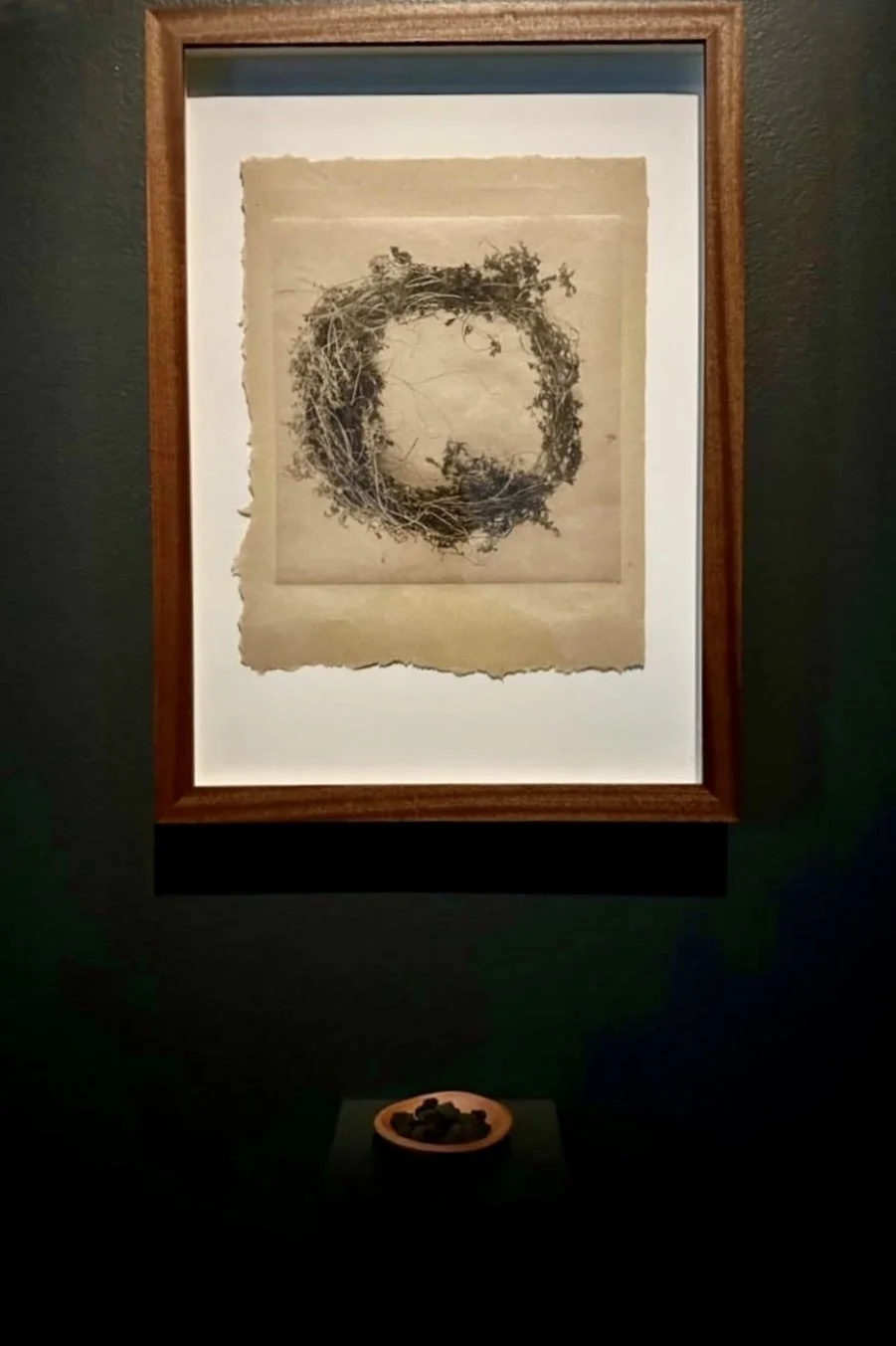

Crown, 2023

Copper photogravure and chine collé printed on gampi mounted on handmade paper made from raffia palm from Cameroon made by the artist, African Sapele wood

Printed by Moonlight Press

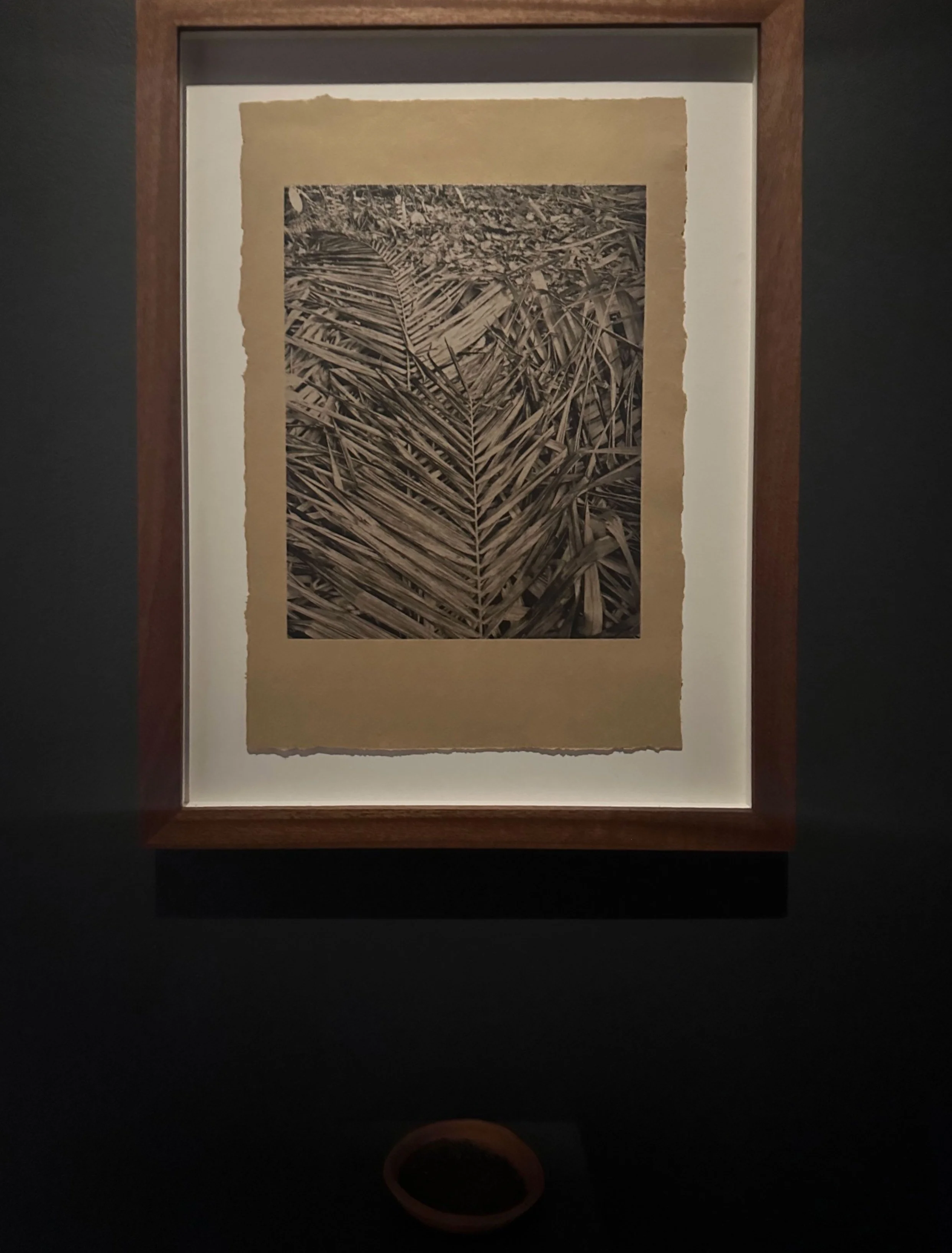

Palms (The Way), 2023

Copper photogravure and chine collé printed on gampi mounted on handmade paper made from raffia palm from Cameroon made by the artist, African Sapele wood

Printed by Moonlight Press

PhotoPolymer Intaglio

The photopolymer intaglio process I use is to create and print images are intentionally ethereal to be in conversation with memory rather than a direct copy. When making these etchings I am trying to fill in the gaps and study the fragments of memory. I depend on techniques like this to remind me, that though it is not possible to see exactly what my ancestors have seen, I can maybe catch a glimpse and experience life the way they might have.

On the right are installation images of Boone Trace (top) and Refuge (bottom) from the solo exhibition Excavation: Past, Present and Future at the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) in San Francisco in 2022. Both of these images were printed on my handmade paper made from raw cotton paper sourced from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina.

Curatorial statement from Excavation: Past, Present and Future at the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD):

Experimenting with early photography, installation, and film, this exhibition invites you to consider the intimate relationship between memory, materiality, and migration.

Inspired by Paul Virilio's The Vision Machine, we may consider the process of image-making as a suggestive practice that evokes a fleeting impression of a time or place. Virillio writes, “the main aim of the heliographic plate is to capture signals transmitted by the alternation of light and shade, day and night, good weather and bad.”

Multimedia artist, Trina Michelle Robinson, combines digital and sculptural practices to interrogate her personal archive and evoke an intimate sense of being with a moment. As a deeply process-driven artist, Robinson considers the sensory and textural significance behind her mediums and calls upon the place from which her materials are sourced. Robinson places special importance on recreating many of the objects that might have once been touched by her ancestors.

For this exhibition, Robinson has included intaglio prints related to her ancestors' forced migration from West Africa, their survival during enslavement in Kentucky, and eventual migration north and west. Robinson further draws on the spiritual tradition of altar-building to create a multimedia installation that provides access into her devotional practice. The paper, made from raw cotton, the terracotta clay of a bowl, and the locally sourced wax of a candle all support Robinson’s exploration of self across time.

Welcoming, St. Helena Island, SC, 2022

Papermaking & Print

Handmade Paper

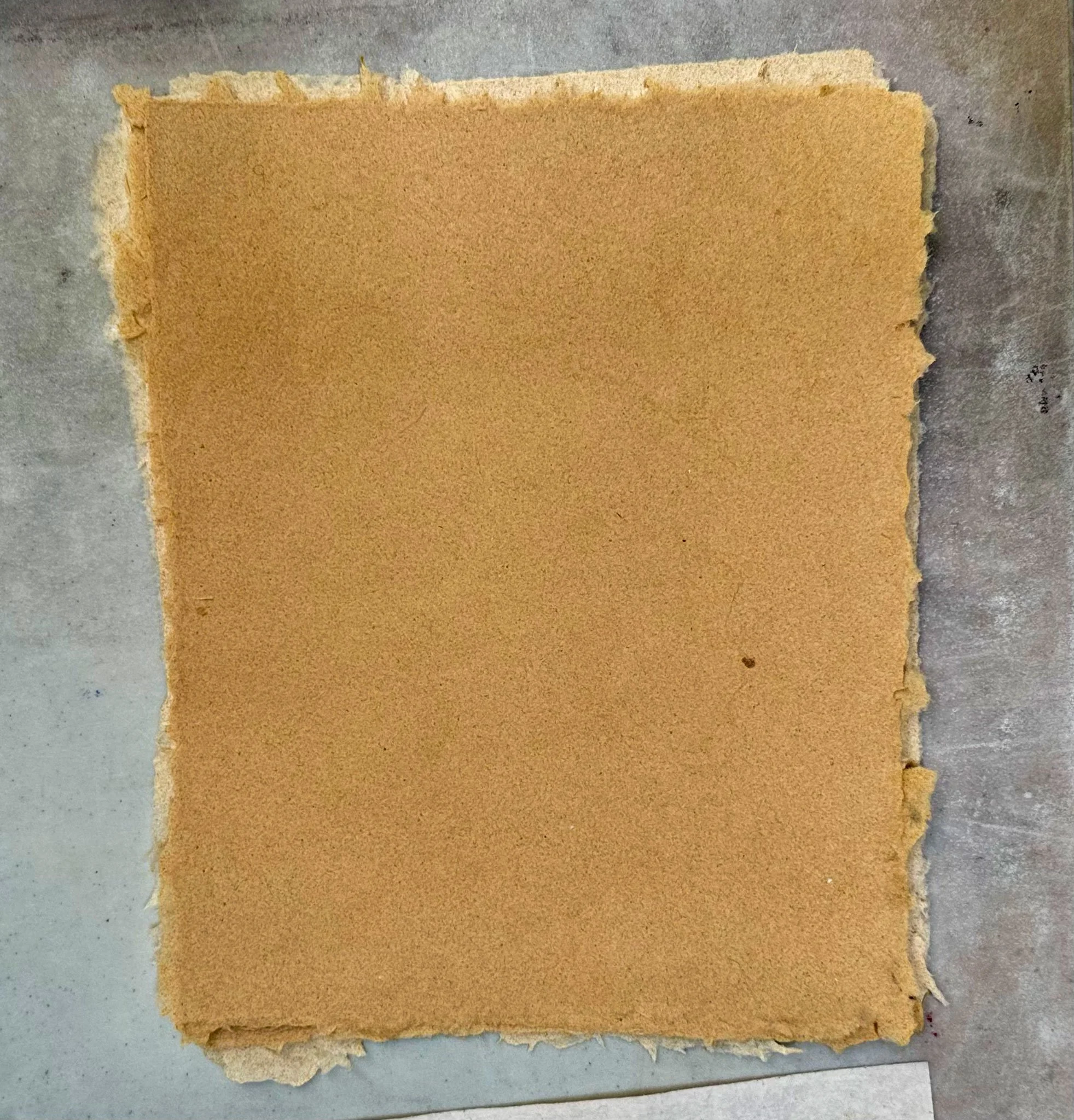

Raw Cotton Paper

The raw cotton handmade paper I create for print projects is sourced from a Black owned farm in North Carolina. The labor intensive process includes me removing the cotton fiber from the bolls by hand, then cooking it to prepare it for the beating process. (You can see documentation of my papermaking process here.)

Using this material is an act to reclaim the material because the brother of my great grandfather owned a farm that also grew cotton in the late 1800s. He worked with the material to prosper and moved away from the narrative of trauma when discussing this material.

Raw Raffia Palm Paper

In March 2023 I traveled to Cameroon and purchased about 30 bundles of raw raffia palm paper to make paper with.

I use this material to connect to my West African roots and the “before”. Before America was even an idea. Before my ancestors came to this place.

PHOTOPOLYMER INTAGLIO And Handmade paper

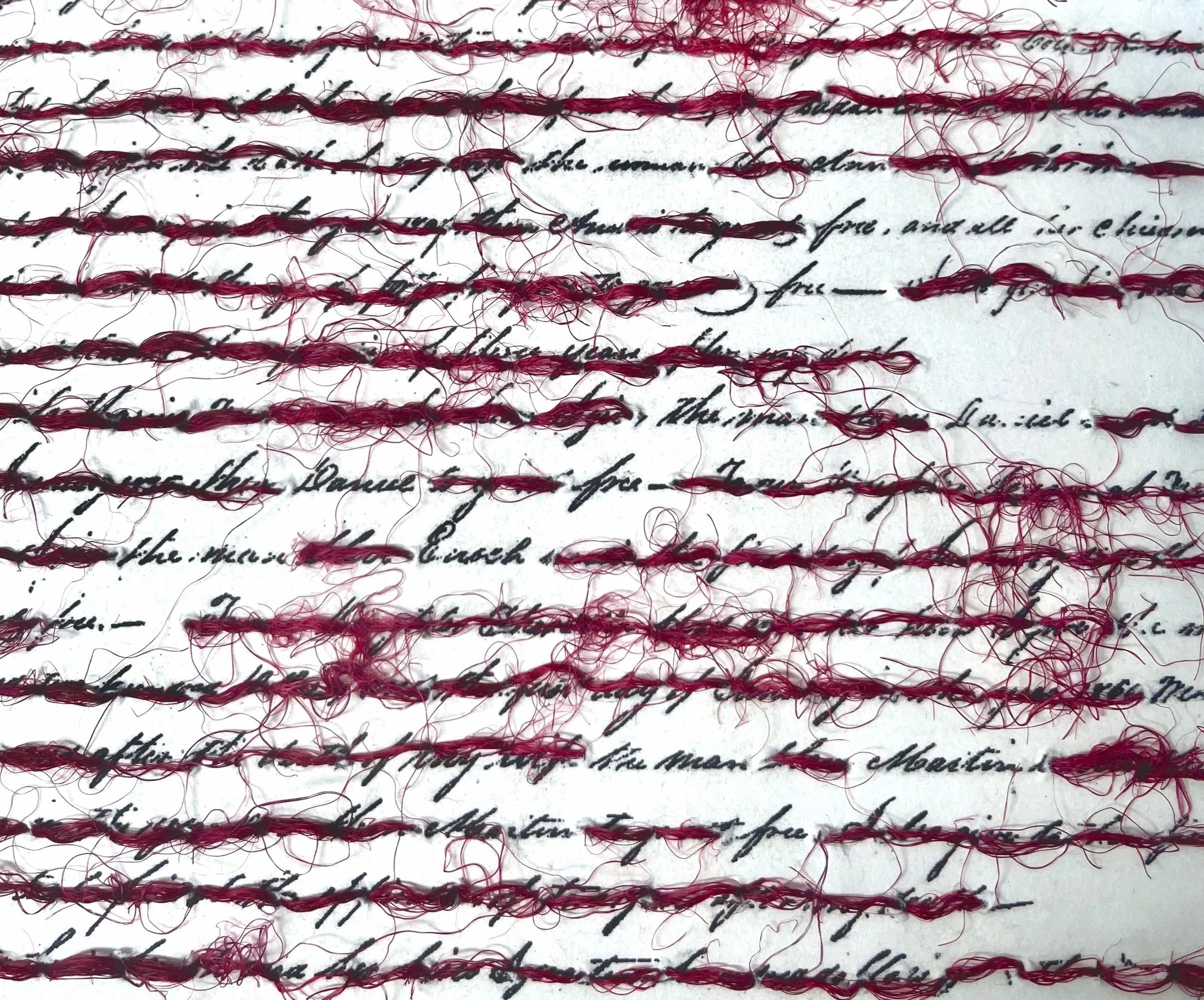

Liberation Through Redaction, 2022

Photopolymer intaglio print, ink made with soil collected from Senegal, charred cedar, bone black dry pigment, sisal dyed with hibiscus from Senegal, raw cotton paper sourced from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina

“The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist. Blackness—

the extended movement of a specific upheaval, an ongoing irruption that rearranges every line—is a strain that pressures the assumption of the equivalence of personhood and subjectivity.” - Fred Moten

While being overcome with grief while deep into the research of the enslavement of my ancestors, I looked for ways to focus on their strength rather than their oppression. This piece is an intimate look at liberation. Through the staining of the hibiscus flower dye, the sisal takes on a wild nature through the tears in the fiber, heightening the redaction/liberation process. A pattern or code built on upheaval is the result.

Seen in the third image is the name of my great-great-great grandfather Martin written in the will of the person who enslaved him mentioning when he will be freed. Using my my handmade paper printed on raw cotton from a black owned farm, hibiscus flower dyed sisal, all sourced from Africa, and ink made from the soil I collected in Senegal, I’ve redacted every word that does focus on my ancestors humanity to take control of the narrative so all that is left in this section is “the man … Martin … free”.

Read more about this piece.

RELIEF PRINT

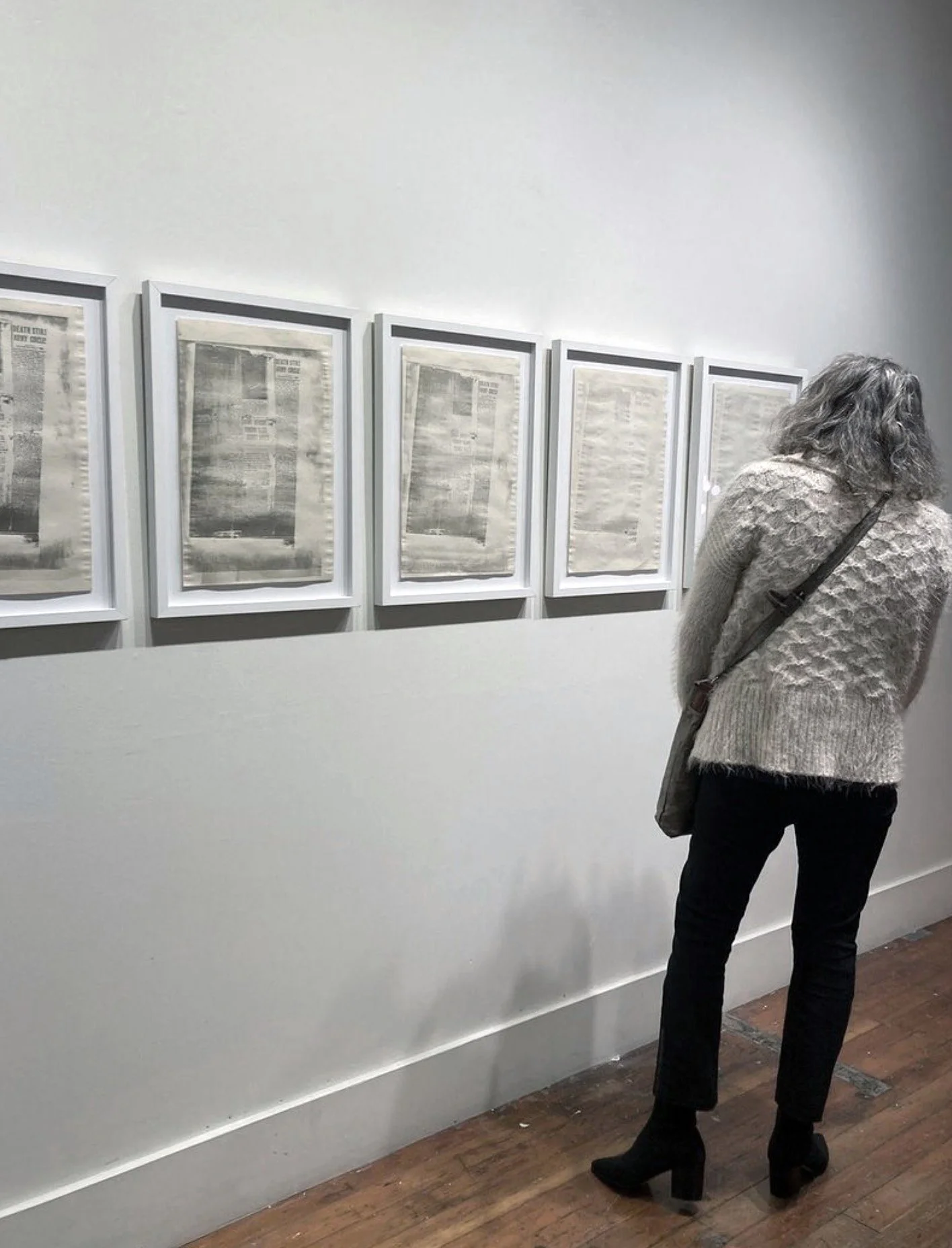

Installation image from the 35th Annual Barclay Simpson MFA Award Exhibition at California College of the Arts, February 2022.

Ghost Prints of Loss, 2022

10in x14in

Relief prints on newsprint, ink made from soil collected in Casamance, Senegal, charred cedar from a border crossing between Senegal and The Gambia, bone black dry pigment, etching transparent base

Installation image from the exhibiton you can hear the wind from beneath the floorboards at Root Division, December 2022.

A relief series of a reprinted January 2, 1932 newspaper article from the African-American newspaper Chicago Defender which was found by my family in a lost photo album after being misplaced for about 50 years. Because I’ve only had access to a distorted photocopy of the recovered original, I decided to create my own. The newspaper article details the mysterious story of Lieutenant William J. French, my great-great-uncle, whose life disappeared from my family narrative following his death in 1932. The handmade ink used is made from charred cedar and soil from Senegal, near the border of The Gambia that I collected while traveling to trace my ancestry. The darker prints also include the addition of dry bone black pigment. The creation of this series of relief prints is the result of my efforts to render my damaged copy a precious personal artifact.

“Ghost print” is a printmaking term when prints made after the original pressing where most of the ink is removed from the plate.

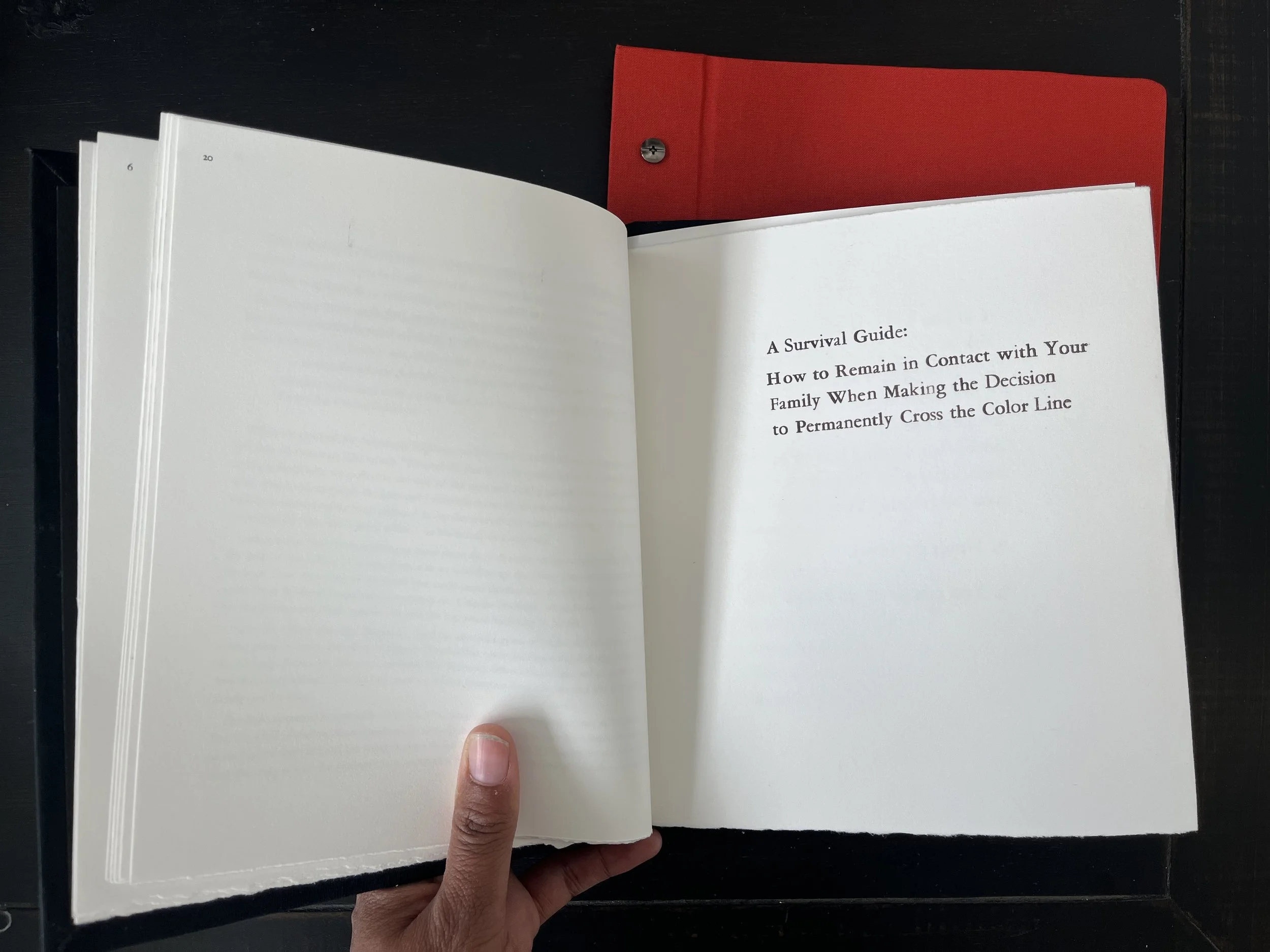

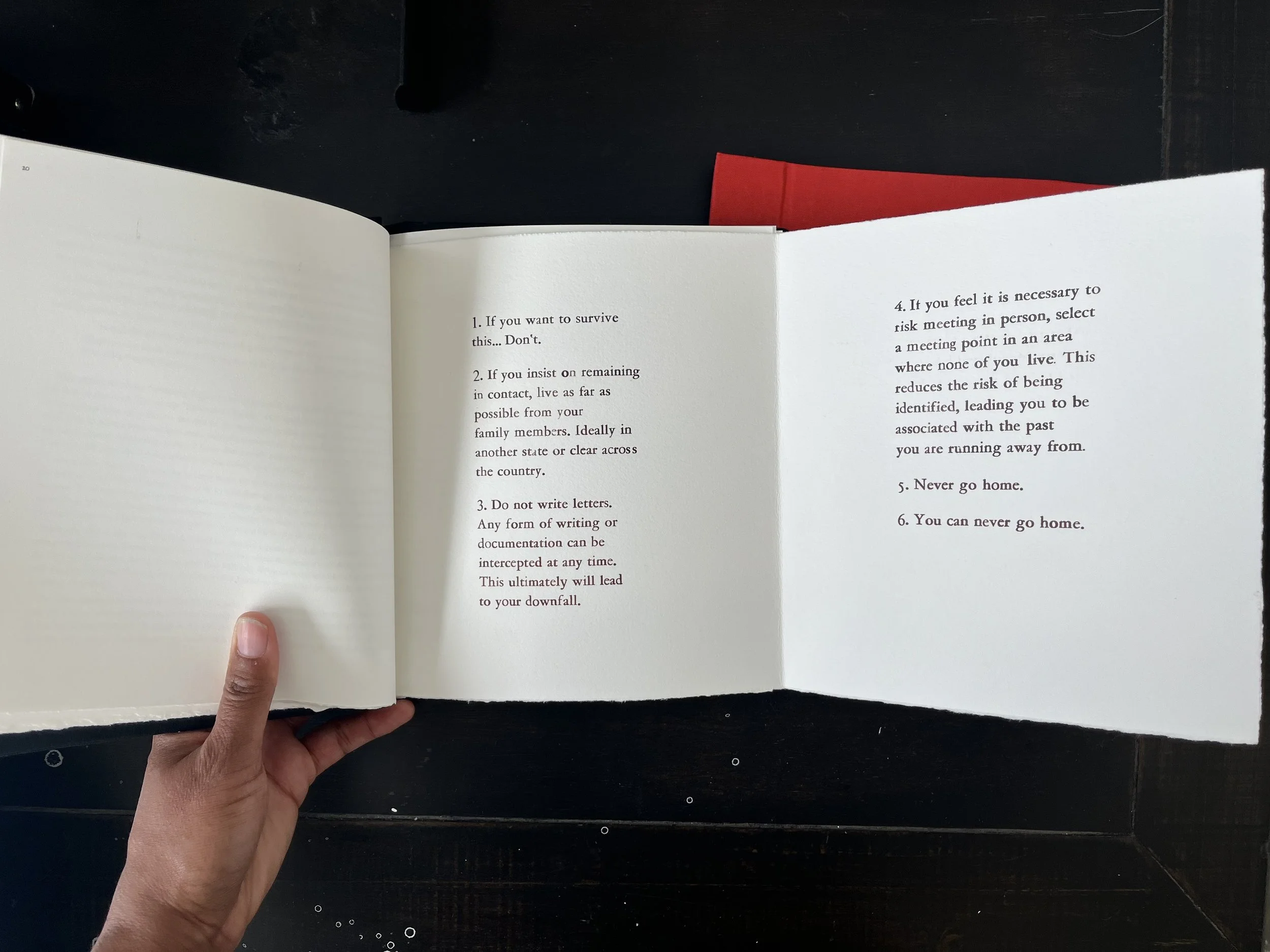

Artist BOOK - Memory Index

Work-in-progress artist book that will be printed using my handmade paper made from raw cotton. The book will also feature photopolymer intaglio and letterpress prints.

This photo album contains the lost memories of a family.

This is a recreation of a family photo album that was misplaced for over 50 years and rediscovered in the late 1990s in the attic of a home of the South Side of Chicago. The original album held family secrets because its discovery opened the door to the long lost details of my family's lives, including their migration to Chicago from Kentucky in the 1860s, generations of enslavement and the crossing of color lines.

The original album contained dozens of long lost family photos from the 1930-40s, in addition to Chicago Defender newspaper clippings from the 1930s.

The recreated album, made with recycled leather-bound front and back covers, contains pages of cyanotypes, plus reproductions and manipulations of original 18th, 19th, and 20th century manuscripts and images telling the stories of the forgotten.

The images below are of the perfect bound version of the album.

Handmade artist book Revival that includes several letterpress pages. (This version is a prototype and an updated version is coming soon.)

Alternative Photography

Installation image from the SFAC Main Gallery 2021 exhibition Taking Place: Untold Stories of the City

Presidio Study I

10” x 14”

Cyanotype on Arches

Presidio Study II

10” x 14”

Cyanotype on Arches

Cyanotype portraits of my great-great Uncle William J. French and the Presidio in San Francisco. I would like to believe that William is my partner in my search for details of my ancestry. I first learned about him in a January 8, 1932 Chicago Defender newspaper article about him that not only revealed that he was passing for white, it also unearthed numbers details that were absent from my family narrative. I feel we are working together to repair what was lost and he is also attempting to make up for the difficult choices he was forced to make.