Liberation Through Redaction, 2022

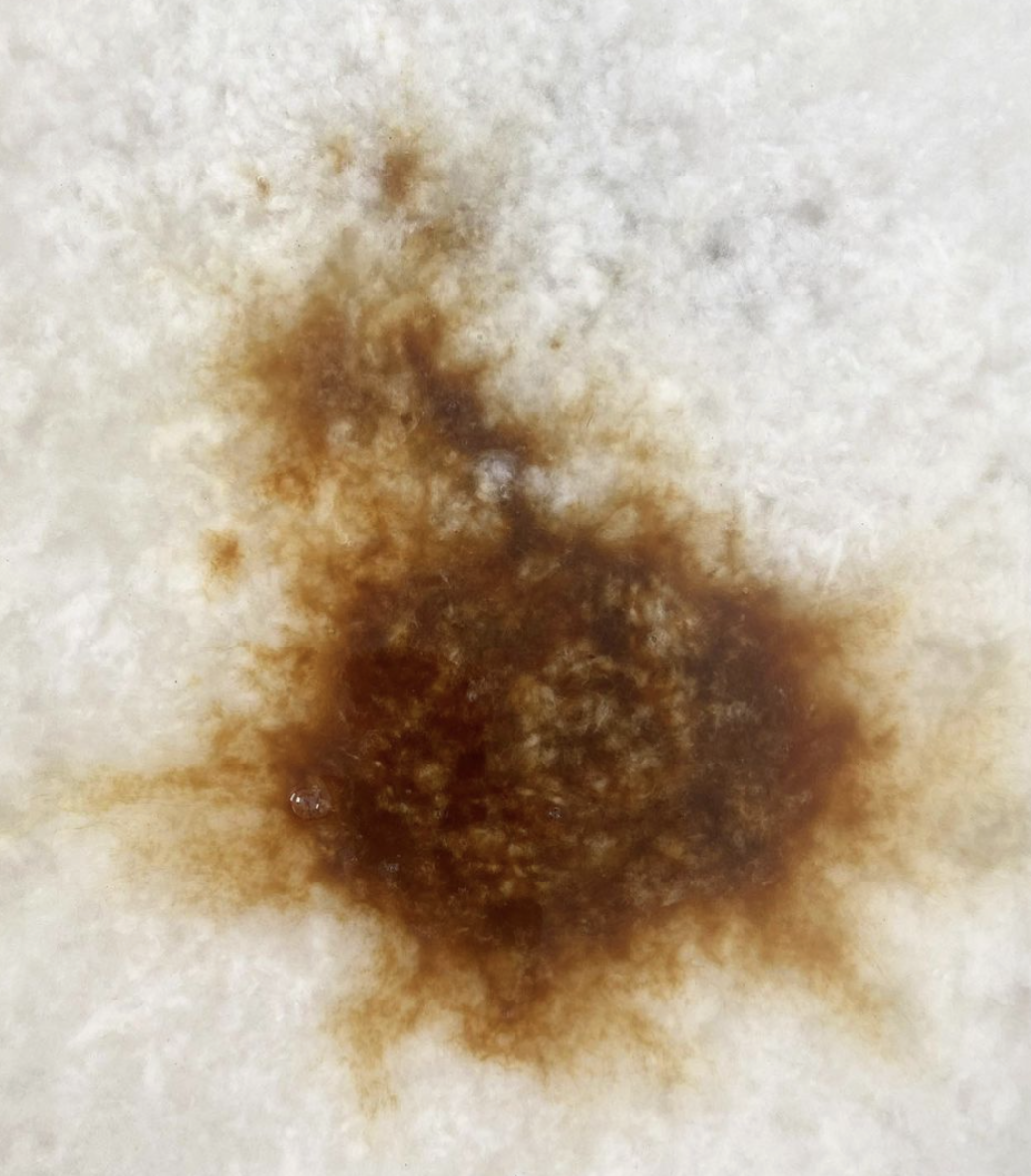

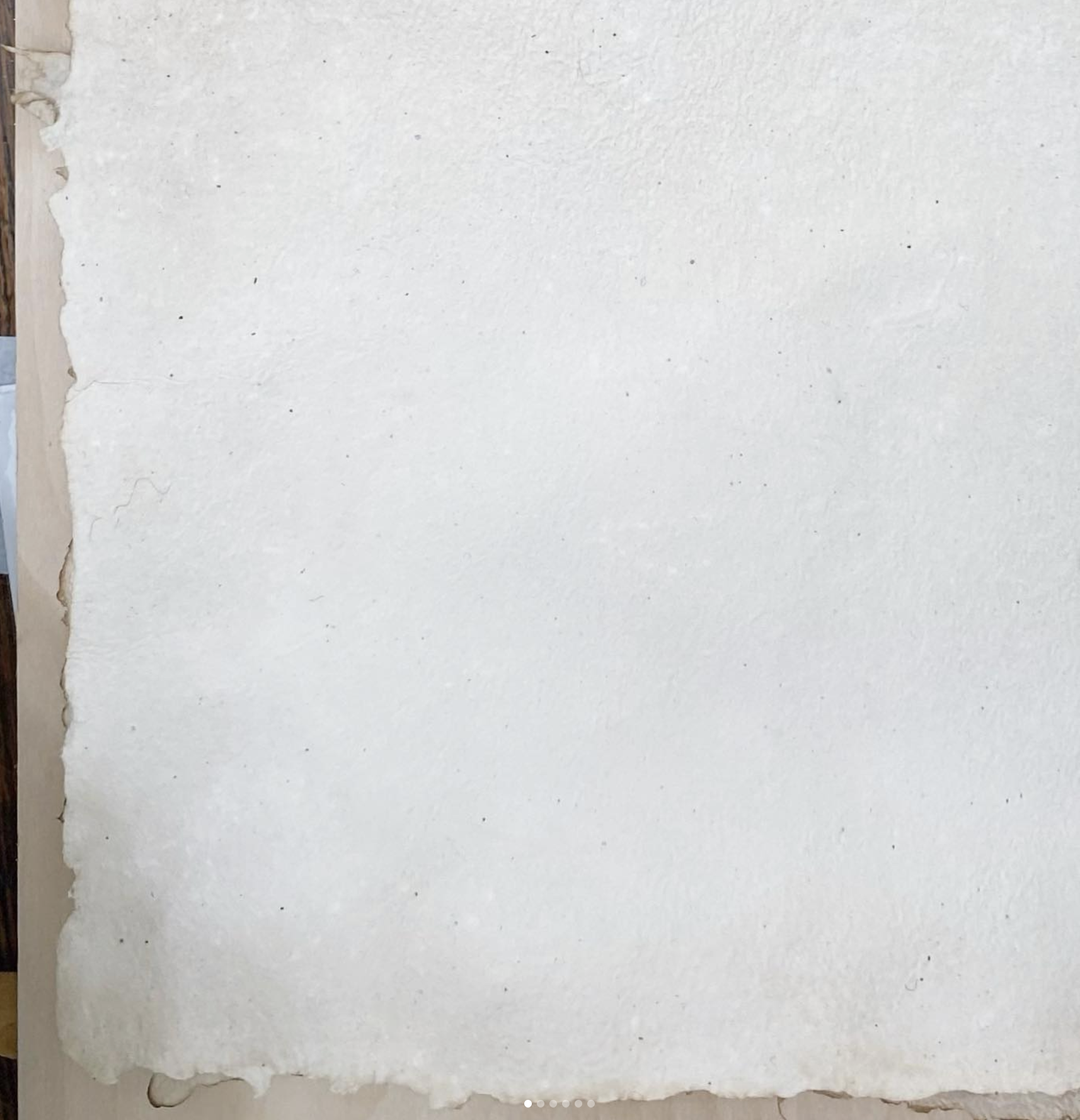

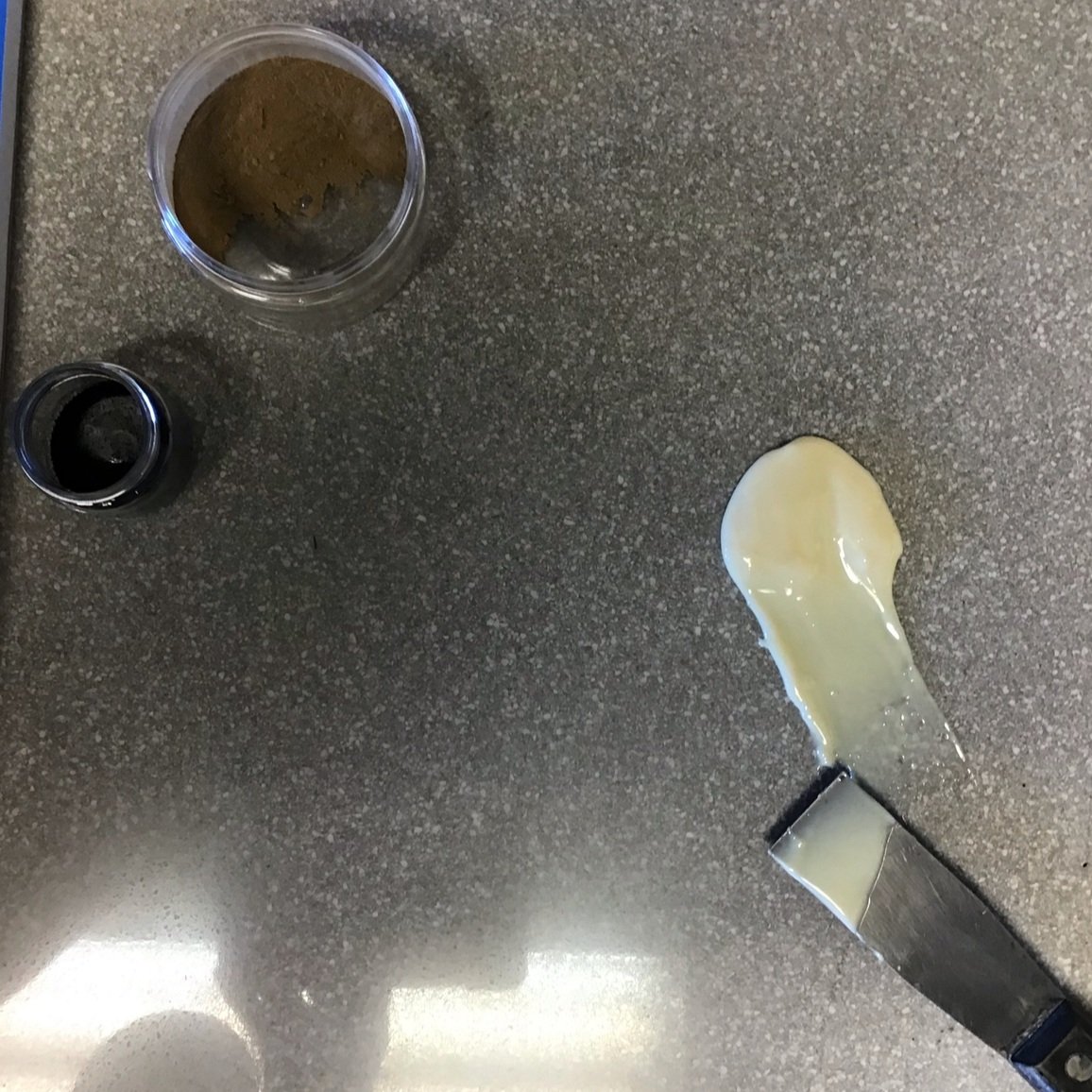

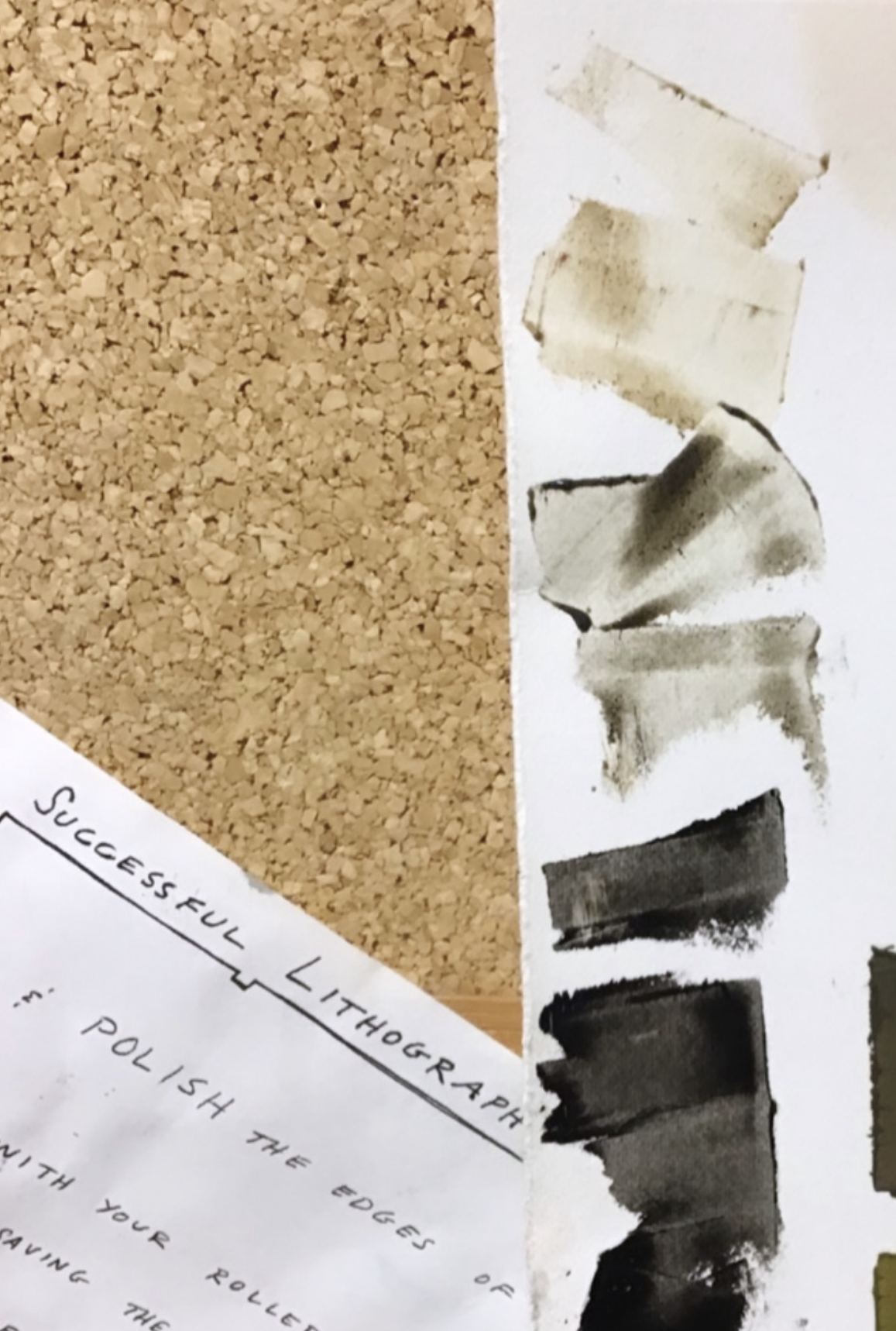

Photopolymer intaglio print, ink made with soil collected from Senegal, charred cedar, bone black dry pigment, sisal dyed with hibiscus from Senegal, raw cotton paper sourced from a Black-owned farm in North Carolina

“The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist. Blackness—the extended movement of a specific upheaval, an ongoing irruption that rearranges every line—is a strain that pressures the assumption of the equivalence of personhood and subjectivity.” - Fred Moten

While being overcome with grief while deep into the research of the enslavement of my ancestors, I looked for ways to focus on their strength rather than their oppression. This piece is an intimate look at liberation.

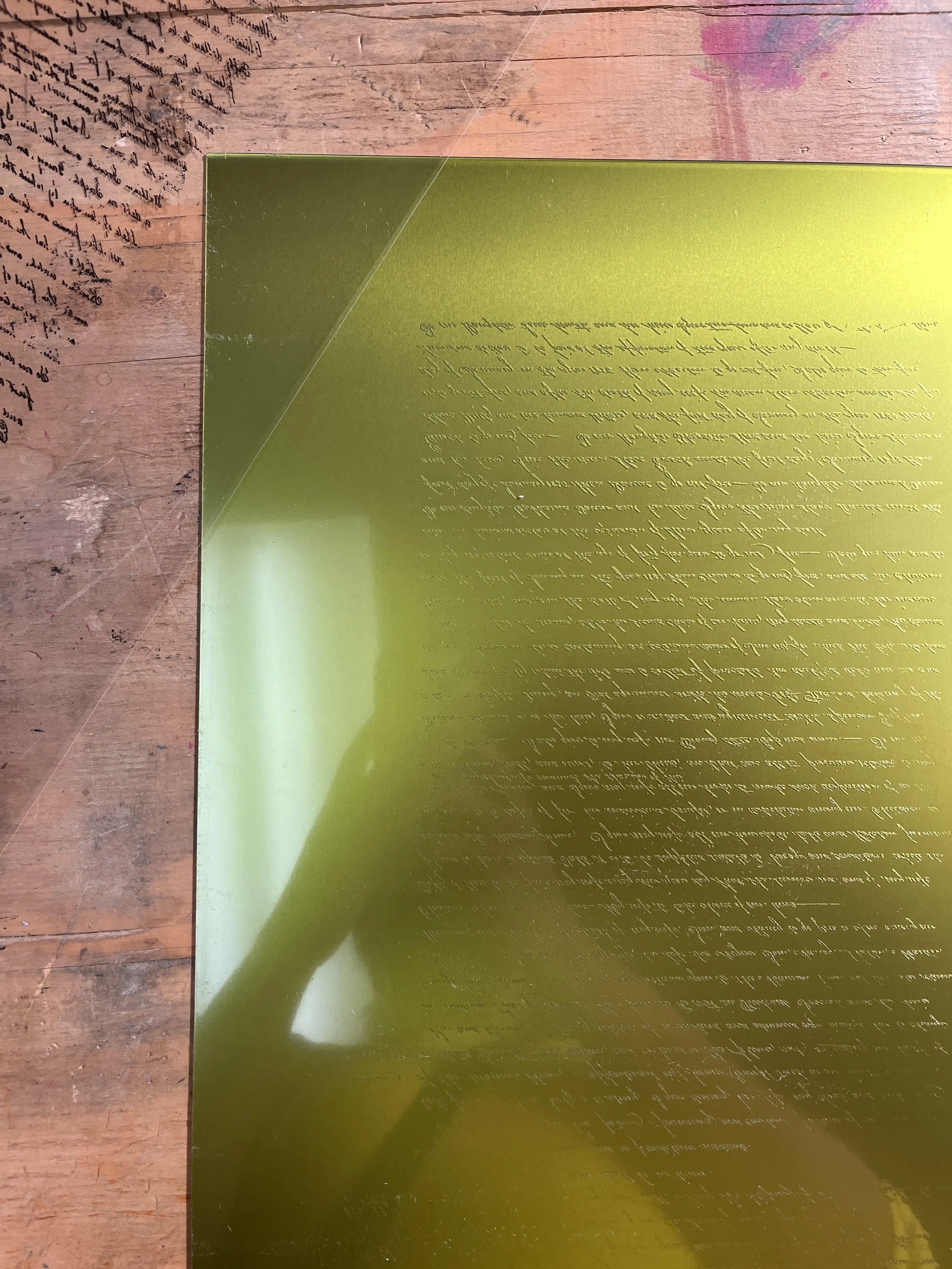

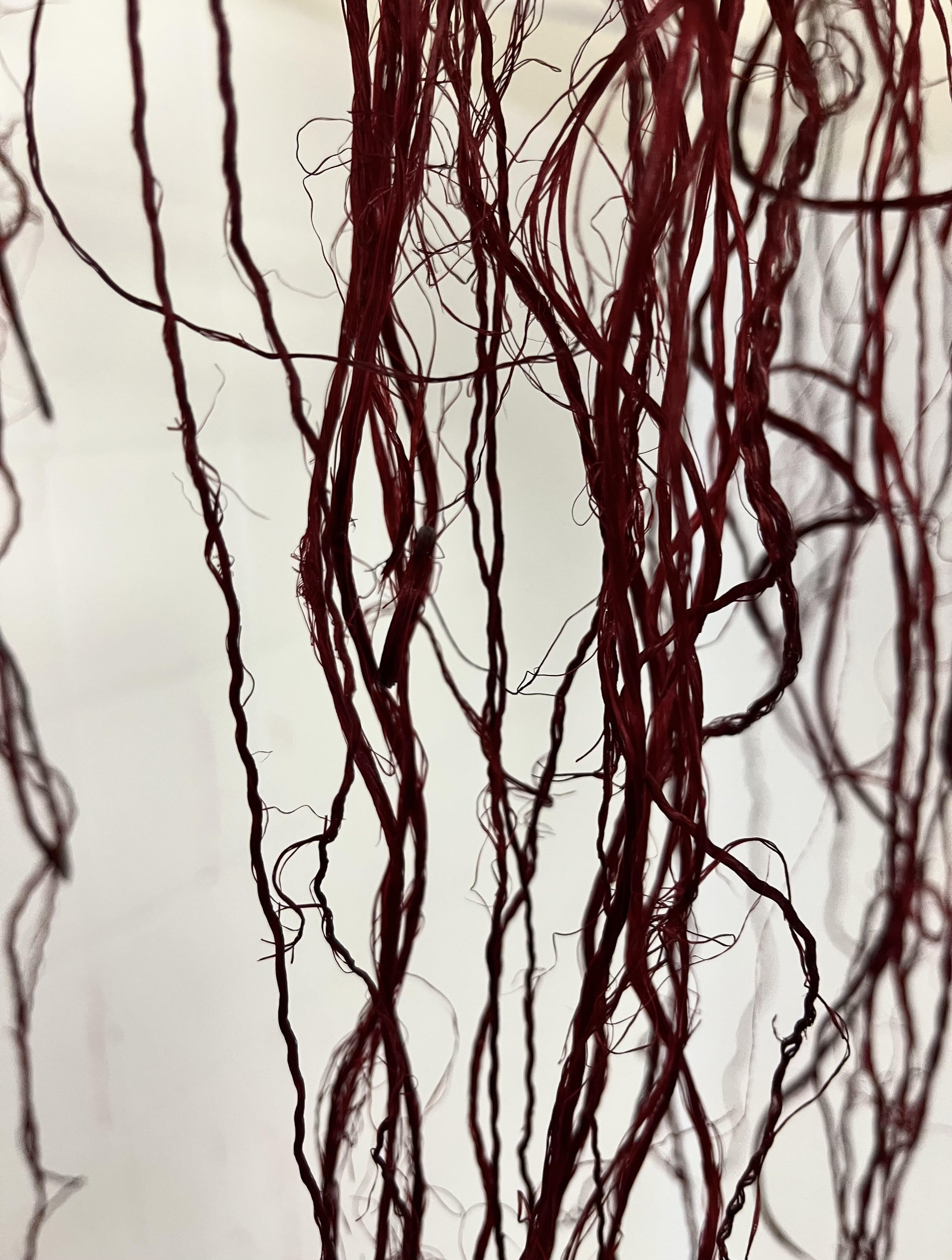

It begins with the 1835 will of a slave owner that lists the enslaved that will be freed once they reach a certain age, usually 45. Among those mentioned is my great-great-great-grandfather Martin and his mother Nancy. Using hibiscus-dyed sisal twine from Zimbabwe, I have redacted every reference to my ancestors' enslavement. The original red hibiscus flowers used for the dye are was purchased by myself at Marché Kerme in Senegal in March 2020, a region I have been able to trace some of my ancestry to using DNA, therefore, the stain of the dye represents the DNA/blood of my African ancestors that continues to flow in the veins of their descendants. (The current version of this piece also uses hibiscus from Senegal but not from the market I visited in Dakar.) Its presence is a constant reminder of their humanity and history, especially while living in bondage. Once stained by the hibiscus, the sisal takes on a wild nature through the tears in the fiber, heightening the redaction/liberation process. The visible punctures in the paper from the hand sewn needle are evidence of the violence of the wound and the fight for liberation. Rebellion is not clean, ordered and tidy. A pattern or code built on upheaval is the result.

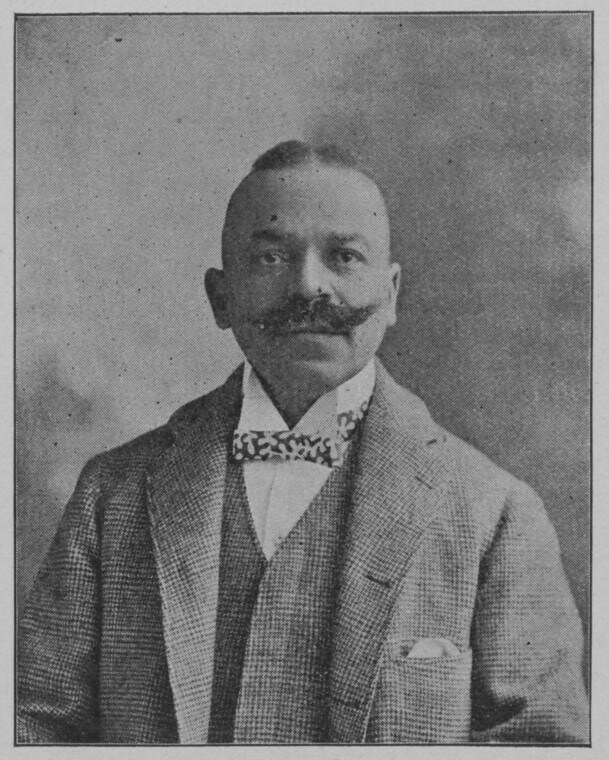

Finally, I made the sheets of paper using raw cotton grown by a Black-owned farm in North Carolina. I processed the cotton by hand, manually removing each seed from the bolls which led to an unexpected grieving process, in addition to an intentional act of reclamation, largely due to the fact that I have an ancestor, John B. French who owned his own farm in Oklahoma that grew cotton and corn for several decades after obtaining his freedom.

Seen in the third image is the name of my great-great-great grandfather Martin written in the will of the person who enslaved him mentioning when he will be freed. Using my my handmade paper printed on raw cotton from a black owned farm, hibiscus flower dyed sisal, all sourced from Africa, and ink made from the soil I collected in Senegal, I’ve redacted every word that does focus on my ancestors humanity to take control of the narrative so all that is left in this section is “the man … Martin … free”.

This piece will eventually include a series of redacted archival documents related to my ancestry.

Documentation

The below images and video detail the process used to create Liberation Through Redaction.

(For mobile phones turn the device horizontally to view captions.)

While in the midst of this project, I came to recognize that it’s creation was truly centered in the “doing”, especially when I was reminded that one of my ancestors, John B. French, the brother of my great-great-grandfather David French, owned ranch in Oklahoma around the turn of the twentieth century where he grew cotton and corn. He is pictured in the last photo.

FILM MIGRATION SERIES

Rather than following my original plan of creating a feature documentary following my efforts to connect to my ancestors, I decided to create a series of video essays that explore that story. I created one film and needed another, then another, to tell the story honestly. Each is focused on a particular idea or event, uncovering the details of the forgotten stories of my ancestors.